KNOXVILLE – The University of Tennessee System ignited action across Tennessee around the opioid epidemic through the first Summit for Opioid Addiction and Response (SOAR).

More than 700 people from various backgrounds came together Thursday and Friday at UT Knoxville to discuss the ongoing opioid addiction epidemic in Tennessee.

“The best way to make the greatest impact on this terrible disease and epidemic is for all of us to bring our collective expertise to the table. I am excited to see all of the big ideas and solutions that will come from this event,” UT Interim President Randy Boyd said.

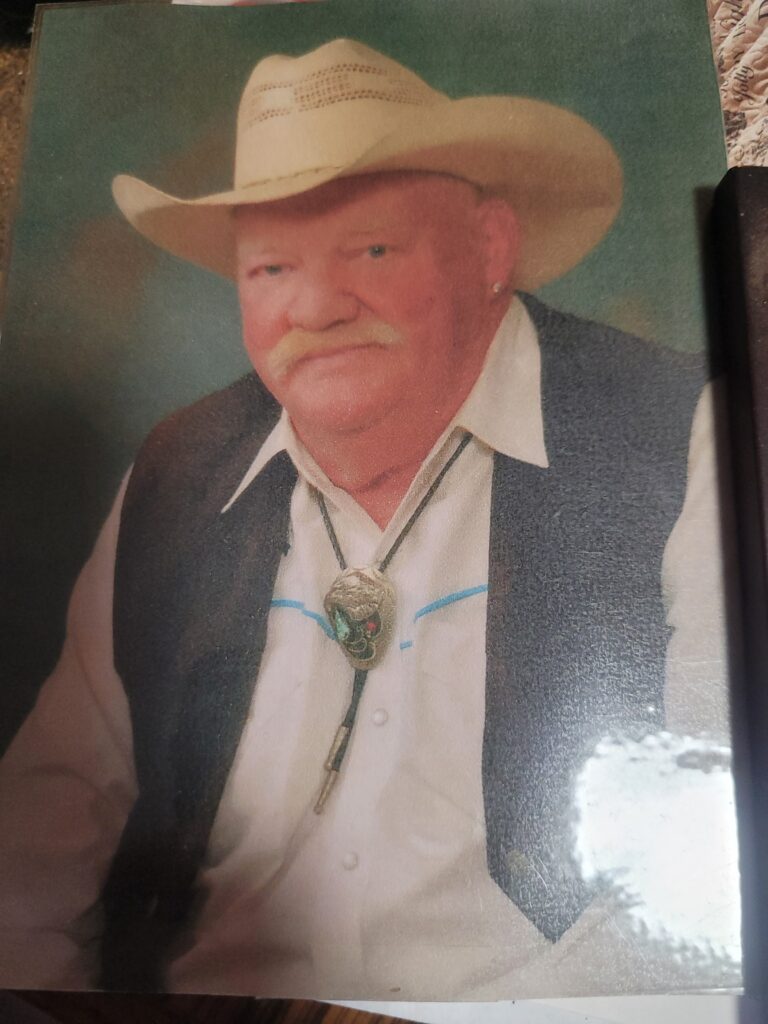

For Knoxville small business owner Jama Williams, the question of solving the crises isn’t academic, but entirely personal. Two of Williams’ children were deeply affected by drug addiction. One of her daughters became addicted to drugs as a teenager. Her son, Curt, became addicted to strong pain medications prescribed by his doctors after breaking his back in an ATV accident.

“We didn’t find out he was addicted for almost a year,” Williams said. “He was so ashamed with himself because he hated what he knew it would put us through.”

Curt went to rehabilitation multiple times but was unable to break his addiction, Williams said. In April of 2015, Curt committed suicide.

“If you can’t have compassion for the addict, please remember they are not the only one suffering… their families and children are suffering, too,”

Williams said. “We need to make changes in order to help society win its battle over drug addiction.”

Dr. Stephen Loyd, medical director for the JourneyPure recovery center, knows the personal struggle of the addict. He struggled with opioid addiction while he was a practicing doctor. However, he sought help and has now been sober for 15 years.

People must be willing to have an open mind and change their ways of thinking about opioid addiction based on new information, Loyd said. If not, the loss of life will only climb higher. “If we keep going the way we are going, more people will die from opioids than all of our wars combined by the year 2023,” he said.

Stigma and shame prevent people from seeking help because society has judged those who do suffer from addiction, Loyd said. Addiction is not a moral failure, Loyd said, instead, it is a chronic brain disorder.

The frontal lobe part of the brain contains insight, judgment and empathy while another part of the brain deals with rewards, he said. When people struggling with addiction finishes a 10-day detoxification, the part of their brain that deals with insight, judgment and empathy still is not working, but the “reward” part is. As a result, they make decisions solely from this “reward” area, which can cause them to relapse.

It takes 100 days of abstinence treatment for those two areas of the brain to start to connect, and two years for the brain to fully recover.

That’s why medication-assisted treatment works, Loyd said.

“When I get a kid coming in that’s been to five abstinence-based programs, and he’s overdosed and he’s been Narcanned four times and he’s 23 years old, I am absolutely going to talk to him about medication 100 percent of the time,” Loyd said. “Matter of fact I’m going to try to talk him into it, because I know it’s his best shot at living.” Narcan, or naloxone, is a medication first responders use to counter the effects of opioid overdose.

Robert Pack, East Tennessee State University professor of community and behavioral health and associate dean for academic affairs, agreed with Loyd regarding his view on medication-assisted treatment.

“Most people believe that medication-assisted treatment prolongs addiction and prevents full recovery. However, research shows that medicated-assisted treatment with methadone and buprenorphine is highly effective in treatment retention and has had a positive impact on mortality, illicit drug use and more,” Pack said.

Experts from across the state continued the discussion on dissolving the stigma and how it affects people’s mental health. Judge Duane Slone, circuit court judge in the 4th judicial district, believes the problem runs deeper than the drug.

“We have to stop chasing the drug and start chasing what drives addiction and suicide, like adverse childhood experiences and trauma,” Slone said.

Clark Flatt, president of the Jason Foundation, agreed. “Thoughts of suicide are much more prevalent in people who struggle with addiction. You’re not going to do away with drug addiction by just doing away with the pills. We have to start providing mental health services as we are fixing this addiction issue.”

Besides devastating lives and families, the opioid epidemic also has affected Tennessee’s economy. UT Knoxville Professor Matt Harris said the opioid epidemic is affecting law enforcement, labor force participation rates and education and human capital formation.

“A 10 percent decrease in prescription opioid use would lead to an additional $825 million in personal income in Tennessee,” Harris said.

He also emphasized that drug-related crimes affect individuals’ lives and property costs and require people to take costly security and personal protection measures they wouldn’t take otherwise.

Because the opioid epidemic has many tentacles reaching into different aspects of society, it is important that the work being done to combat the crisis does not occur in isolation. This is the main point Karen Pershing, executive director for the Metro Drug Coalition, and Carla Saunders, founder and CEO of the healthcare nonprofit One Tennessee, discussed in their presentations.

“It is imperative that we work together to increase prevention,” Pershing said. “Adolescents who begin using any substance before age 14 are 17.5 times more likely to have a substance use disorder as an adult, compared to 2 percent if abstinent though graduation.”

Saunders continued the conversation by emphasizing the power one voice can make, which could then impact the futures of countless lives. The former nurse practitioner at East Tennessee Children’s Hospital noticed an increase in the number of babies in the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) who were showcasing symptoms of withdrawal. As a result, Saunders created one of the first treatment protocols for babies exposed to opioids.

“I was just one nurse practitioner in one NICU unit, but out of that came the neonatal abstinence syndrome program,” Saunders said. “Never underestimate the power of one voice. One individual interaction with another can change the trajectory of one life. The power of one collective voice can change the trajectory of the future.”

Darren DeArmond, assistant special agent-in-charge for the Tennessee Bureau of Investigation, agreed this epidemic cannot be solved by law enforcement.

“We can’t arrest this problem away. No matter how many times we arrest them, they are going to end back up on the street. It’s a partnership. We have to work together,” DeArmond said.

The discussion around collaborative efforts continued with a working lunch surrounding sequential intercept mapping (SIMS). SIMS identifies opportunities for screening, treatment, diversion and overdose education for opioid users at risk of overdose. This framework includes not only treatment services but also crisis response services, prevention and regulation, such as community-risk assessment, accessible prescription drug drop-off sites and medication-assisted treatment.

The two main goals of SIMS for the opioid crisis is to encourage counties to organize their efforts and assist counties in choosing its efforts from different sectors based on evidence-based or best practices.

In accordance with the idea of more collaborative efforts, the UT System had a call to action in the development of an asset map so the work happening across the state will not continue to be done in isolation. By using this feature, people would be able to hover over any community in Tennessee and see what resources are available in areas across the state.

“Together, we can develop solutions that permanently break the cycle of addiction in our communities across the state. Together, we can transform those affected by this opioid epidemic. UT is for all Tennesseans, and we are here to help change lives,” Interim President Boyd said.

Other panelists and speakers included:

Monty Burks, director of faith-based initiatives, department of mental health and substance abuse

Jan Clift, survivor of a drug-related shooting

David Rausch, director, Tennessee Bureau of Investigation

Keith Gaither, director of managed care operations, TennCare

Lisa Piercey, commissioner, Department of Health

Matt Yancey, deputy commissioner, community behavioral health programs, Tennessee Department of Mental Health and Substance Abuse Services

Jim Casey, director of behavioral health services, Tennessee Department of Corrections

Jeff Long, commissioner, Tennessee Department of Safety and Homeland Security

Jennifer Nichols, commissioner, Tennessee Department of Children’s Services

Michael King, regional administrator, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration

Betty-Ann Bryce, public health, education and treatment – rural lead, Office of National Drug Control Policy

Sharon K. Davis, clinical assistant professor for the UT Knoxville College of Nursing.

Justin Crowe, extension specialist for the UT Institute of Agriculture.

Karen Derefinko, assistant professor of preventative medicine at the UT Health Science Center in Memphis.

Jerry Jones Jr., assistant professor and division chief for the regional anesthesia and acute pain medicine at the UT Health Science Center in Memphis.

Shandra Forrest-Bank, UT Knoxville director of the social work office of research